Kerri Battles the AFI’s Top 100 — #74: The Silence of the Lambs

“Good evening, Clarice.” It’s one of the great misquoted movie lines of the 21st century. It’s right up there with, “No. I am your father.” But it exists within a movie I’ve seen far fewer times. In fact, before this weekend, I wasn’t certain that I’d ever actually seen The Silence of the Lambs in its entirety and in one sitting. When you’re as big a fan of Movies as I am, a question like that will nag at you, particularly with a movie so culturally pervasive as this one. Finally sitting down and removing all doubt is like finally being able to scratch that itch that started on the bottom of your pedal foot while you were driving on the highway. Satisfying doesn’t quite begin to describe it.

… No… that REALLY doesn’t describe it, either…

The Silence of the Lambs focuses on an ambitious young FBI Academy student, Clarice Starling, who is hoping to make a name for herself in the Behavioral Science Unit. When her teacher and BSU agent, Jack Crawford, asks her to interview infamous serial killer Dr. Hannibal “The Cannibal” Lecter, she jumps at the chance. Her goal is to consult the brilliant and beyond-insane Lecter on another case: Buffalo Bill, the guy who keeps killing chubby chicks and skinning their pieces. Clarice develops something of a rapport with Dr. Lecter and begins to suspect he knows Buffalo Bill personally. When Buffalo Bill abducts the daughter of a Senator, Clarice (per Crawford), offers Lecter a deal — if he gives them Buffalo Bill’s real name, the Senator will approve his transfer to a cell with a view. The deal’s a fake, but the Senator makes it real when she finds out her name was used without her knowledge. Finally, Lecter gives a name: Louis Friend. Clarice spots it immediately as a fake and works it out to be an anagram of Iron Sulfide. Fool’s Gold. Her visitation rights revoked, Clarice sneaks in to Lecter’s temporary holding area and begs for the name. As she’s dragged out by local cops, Lector gives back Bill’s file and tells her all the info she needs is inside. Ten minutes later, Lector brutally murders two of those cops, wears one of their faces like a mask, and escapes. Clarice discovers, with the help of Lecter’s cryptic notes, connections in Bill’s file that hadn’t been explored before. Through a wacky boy-is-my-face-red turn of events, she finds herself alone in the home of Buffalo “Makin’ a Woman Suit Out of Women” Bill without backup. Clarice almost dies, but kills Bill and saves the girl instead. When he calls to express his congratulations, Lecter tells Clarice he has no intention of coming after her and he would appreciate the same courtesy. Then he heads off into the sunset to eat the Smug Pompous Warden from Act I.

Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs is to the world of movies what The Beatles are to the world of modern music. Neither is particularly innovative or progressive. In fact, both are fairly simple and accessible to all audiences. But both take simple and accessible and do it masterfully, in a way that allows them all to continue to reach audiences long after their times. For The Beatles, it’s just the right harmonies and strategically placed “oooohs” or bass lines that keep modern bands listing them as an influence. For Demme, it’s the perfect extreme close up or the minute details the FBI consultants ensured were accurate. It’s his way of simply describing or showing reactions to gore so that the little bit of viscera he finally does show has real impact. It’s the way he builds the charming and beyond-classification-crazy Dr. Lector character, then yanks him away mid-movie, reminding us that — oh yeah! — we’re supposed to be finding that maniac who keeps dropping skinless women in rivers. And it’s the way he then builds the suspense all over again until Clarice is grasping around in a blackened basement while Buffalo Bill watches from inches away through night vision goggles. The Silence of the Lambs isn’t perfect, of course. No Pop Culture icon is flawless — even The Beatles had “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” — and different groups seem to have pretty vocal opinions on which flaw is most in need of correction. We could debate the merit of these claims all day, but it would be nothing more than a distraction from the most disturbingly inaccurate portrayal of all.

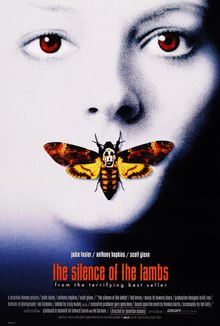

The above photo is a screencap of the opening credits. For the first few minutes of the film, their appearance on screen at regular intervals dominates the view. They’re jarring, obscuring and distracting from the action occurring behind them. This specific title credit, though, is perhaps the most distracting, especially at the time of release. Think about it. It’s 1991. Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game” video is basically playing on a loop on MTV. You know the one — that little black and white short featuring the musician himself rolling around on a beach with a topless Helena Christensen that causes men and women to stop, gasp, and stare. To see his name in bold and imposing letters on screen like this makes you think he’s going to have an important role in the film, if not a large one. Paul Lazar and Dan Butler, for example, play Pilcher and Rodin, the scientists who identify the rare moth from the poster for Clarice. They provide the only, much-needed comic relief in the film and are ultimately instrumental in the success of Clarice’s search for Buffalo Bill. They’re not major characters, but they are imperative to the progression of the plot. Chris Isaak, on the other hand, plays “SWAT Commander” and has about 4 lines in his maybe minute and a half of screen time. Aside from his very recognizable face, he’s almost indistinguishable from any other cop in the solitary scene in which he appears. He doesn’t even die gruesomely at the hands of an escaping Lecter! He appears on screen in a feeble moment of blatant stunt-casting, points at his eyes and makes some gestures with his fist like SWAT guys are supposed to, then fucking disappears again for the rest of the film. There were easily hundreds of other actors in Hollywood in 1991 who would have seen that amount of face time in this movie as a pretty big break! So what the hell was Demme’s motivation behind giving it to a guy whose face was just pretty and famous enough to divert attention from the action and suspense at hand? The world may never know. I presume incriminating photos of some kind or another. — KSmith