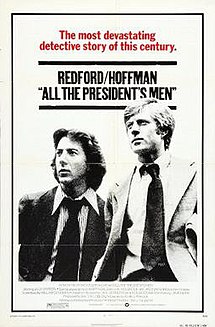

Kerri Battles the AFI’s Top 100 — #77: All the President’s Men

I hope you’re all ready for some serious fan-girling this week because we’ve hit a high point on The List with a film I’d put in my personal Top 25, at least. The first time I watched All The President’s Men, I was about halfway to earning a degree in film and completely disillusioned with the prospect of trying to make a living as a screenwriter. I have been writing in some way, shape, or form since I first learned to draw letters on paper and Screenwriting 101 was the first time I had ever been told my writing was too descriptive and needed to be pared down. It felt counterintuitive, particularly since the defense was, “The director tells the story. The screenwriter just provides him the tools to do so,” and I really, really didn’t like it. At a perceived crossroads in life and possibly not yet able to even legally drink, I stumbled upon All The President’s Men during the opening credits on cable. For the record, colored through the young writer’s ennui of quarter-life-crisis-glasses is probably the best way to view this film. Having said that, there’s still no scenario in which, when the final credits roll, you don’t want to become a beat reporter on the Metro desk in the nearest big city.

In June, 1972, five guys broke into the Democratic Headquarters in the Watergate building in Washington, D.C. with the intent of bugging the room for the benefit of the Committee for the Re-Election of the President (that’s Nixon, kids). Thanks to an observant security guard and some sloppy-ass burgling, they were arrested pretty damn quick. While covering the indictment for the Metro desk of the Washington Post, a ravenous young reporter named Bob Woodward hears one of the defendants quietly inform the judge that he’s retired CIA. Adding that to their expensive attorneys and the many hundred dollar bills they were arrested with, Woodward began to suspect that this might be more than just your average smash and grab. Joining forces with the equally hungry Carl Bernstein, the two spend the next half a year catching every inconsistency and following up on every lead, constantly trying to reconcile what seems blatantly obvious with what they can actually prove. Woodward meets a double-secret source called Deep Throat in a deserted parking garage in the Virginia suburbs at 2am, who keeps him pointed in the right direction. They promise anonymity to all sources and lie about what they know in order to elicit confirmations of what they only suspect. Editor Ben Bradlee swears a lot and tells them repeatedly that they need harder proof. Finally, Deep Throat tells Woodward that their lives are in danger because this thing goes all the way up. When Woodward and Bernstein show up at Bradlee’s house in the middle of the night to warn him of the peril, he says, “You guys are probably pretty tired, right? Well, you should be. Go on home, get a nice hot bath. Rest up… 15 minutes. Then get your asses back in gear. We’re under a lot of pressure, you know, and you put us there. Nothing’s riding on this except the, uh, first amendment to the Constitution, freedom of the press, and maybe the future of the country. Not that any of that matters, but if you guys fuck up again, I’m going to get mad. Goodnight.” We see Woodward and Bernstein furiously typing the articles that would blow the lid of the grandest and worst political scandal of modern times as the television airs Mr. Nixon taking his oath for the second time. The film concludes with an extreme close up of a teletype machine relaying the headlines over the next year and a half, culminating in Nixon’s resignation.

You sure about that, buddy? You wanna maybe think about your answer a little bit more and try again later?

An exorbitant amount of effort and money was spent making this film (almost) as accurate as possible. Incredible tech and production tricks were used to make the visuals just as engaging as the story itself. Redford, Hoffman, Robards, Jack Warden, and Jane Alexander all provided impressively nuanced and impeccable performances. These are the sorts of things that will help a film win awards left and right and get recognized by the likes of the American Film Institute. And, sure, these are also often the things that will cause a movie to live on in the collective consciousness that is the Pop Culture Hive Mind. But All The President’s Men has something going for it that easily puts it ahead of the pack. It’s the story of honest and good heroic types who fight against the villainous The Man for the greater good and actually win. It’s the great romantic modern-day true legend that combines the best parts of King Arthur, David and Goliath, and reality to perfectly explain why an independent free press is necessary to maintain an informed populace and a free and democratic society. It’s the most important story to drive altruistic young writers to Journalism school since Nellie Bly faked insanity to get committed on purpose and show the world how truly horrific asylums really were. The world will always remember that Richard Nixon was actually very much a giant fucking crook, despite his proclamations to the contrary. But that wouldn’t be the case if it weren’t for Bob Woodward, Carl Bernstein, Ben Bradlee, and former Assistant Director to the FBI Mark Felt, aka Deep Throat, steadily blowing the whistle on every incriminating detail they could verify.

I never ended up changing majors in college. Mainly, it was because my advisor informed me that it would mean being in school for another four years and, given that I was already projected to drown in student loan debt before I would ever comfortably retire, it didn’t seem like the prudent choice. When I watch the news, I’m generally pretty confident with that decision. These days, journalism has become so yellow that the guys who crack jokes on Comedy Central and HBO seem to be the most honest newscasters around. Even the ghosts of Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst think Ted Turner and Rupert Murdoch have taken this ratings war thing too far. Every once in a while, it all gets to be too much and it seems like DoubleThink has become the accepted norm, I’ll pop on All The President’s Men and think, “It wasn’t that long ago. It’s possible that journalists out there still possess this kind of courage and integrity… Right?” … Sometimes I believe it. And sometimes I just want to start a revolution by A Clockwork Orange-ing Bill O’Reilly with old footage of Edward R. Murrow and Walter Cronkite… That’s probably an unrelated issue.– KSmith